THE STORY BEHIND THE STORY: In 1996 we thought motocross design had leveled off. After 25 years of rapid change, it seemed that new technological innovations were few and far between. With this story, we attempted to document how far we had come. The idea was to evaluate various design innovations in terms of lap times. The problem, obviously, was finding test bikes that were in good enough shape to provide an accurate test. Our original wish list included more bikes between 1976 and 1986, but this proved impossible given the time constraints of a monthly print magazine. The bikes we had were the bikes we had. Several came from Rick Doughty’s Vintage Iron, and some had to be restored for this project. The 1981 Suzuki RM250 had a fascinating back story. It had been used as evidence in Richardson vs. U.S. Suzuki, a court case where the original designer of the Full Floater filed a lawsuit against Suzuki for patent infringement. He won. This bike had been sitting in his partner’s airplane hanger since then, brand new but missing parts. Here is the resulting story, which originally appeared in the September, 1996 issue of Dirt Bike.

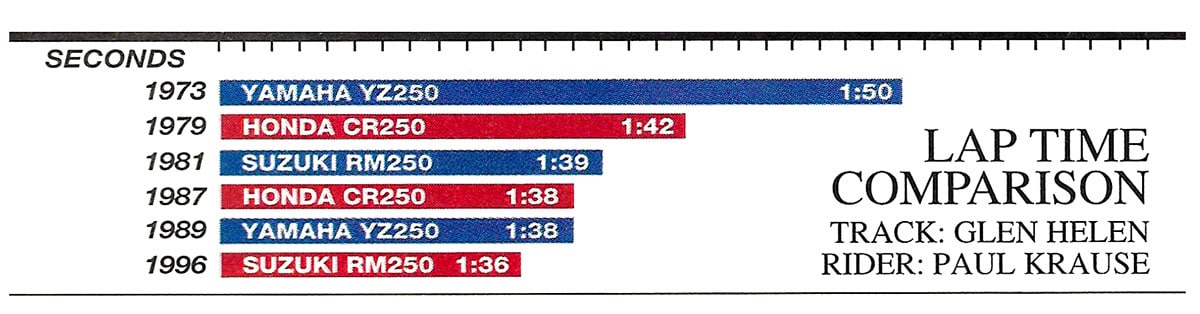

We accept that technology has made bikes steadily and significantly faster, but who knows how much faster? Which was more important, disc brakes or liquid-cooling? How about long travel suspension versus rising-rate linkage? We got bikes from six major steps in the advancement of dirt bike technology and put them together at once. Paul Krause test-rode each bike to measure the difference and to see how much progress was made at each step of evolution.

’73 YAMAHA YZ250: MOTOCROSS-SPECIFIC DESIGN

By 1973, makers accepted that motorcycles intended for motocross had to be purpose-built. Most of the details were still a work in progress. Yamaha’s late-’73/early-’74 YZ250 was a marvel of technology in its day. It was far better adapted for racing than anything before it, and yet many of its features still revealed some similarities to street bikes of the time.

By modern standards, the YZ’s limitations are easily spotted. The skinny 36mm fork, tiny frame tubes and small overall size might have trimmed the YZ’s weight to 211 pounds–15 pounds less than a modern 250 motocross bike–but caused numerous shortcomings. The YZ easily used up its suspension travel (7 inches in front and 4 in the rear). The pounding was enough to warn the rider to back off early.

The YZ’s engine offered much more than its chassis did. Its single-cylinder, air-cooled, two-stroke engine was light, narrow, and respectably powerful for its day. At a time when vulnerable downswept pipes were common, the YZ had a through-the-frame, upswept expansion chamber that stayed out of harm’s way. Yamaha’s use of reed valves on the YZ gave the bike cleaner, more solid power delivery than the piston-port engines of its time.

During the initial laps on the YZ, the bike gave the impression that it had a great deal of power. In reality, it just put out enough power to overwhelm its chassis on most parts of the track, so it seemed faster than it was.

1973 YAMAHA YZ250 LAP TIME: 1:50

’79 HONDA CR250: LONG-TRAVEL SUSPENSION

Motocross bikes had clawed up to their first major design plateau by the late ’70s. Following an awkward growth period, suspension travel had leveled off around 12 inches, and chassis design had finally become compatible with that much travel. For the first time, dirt bikes had followed a design path that was completely separate from street-bike thinking. In the process, an entirely new type of motorcycle had arrived.

The ’78 and ’79 Honda CR250R were among the first to integrate long-travel suspension into their designs. Most of the bike might look wimpy by current standards, but was impressively sturdy for its day. The offset-axle fork had long travel and enough overlap to adequately resist binding and breakage. Our test bike had an aluminum aftermarket swingarm and Works Performance shocks, but the ’79 CR’s nitrogen-charged stock shocks and box-section steel swingarm were race-worthy in their day.

Long-travel suspension was a big upgrade, but steering response got vague when the long, thin 38mm fork twisted in ruts. The bike still handled quickly and predictably on other parts of the track. The only drawback to the CR’s new rear suspension was the width created by the top shock mounts. It stopped the rider from moving freely on the machine.

The basic configuration of the CR’s air-cooled, two-stroke, reed-valve engine was very similar to the ’74 YZ250’s, but its performance was very different. It had a sharper, quicker power delivery with fuller midrange response. The ’79 was good for 30 horsepower on the dyno. That wasn’t much different from the peak power of the ‘74 model, but it had a much broader powerband. It was around ten horsepower less than a typical ’96 250.

The ‘79 Honda’s suspension was largely responsible for its quicker progress around the track. The dramatic reduction in lap times compared to the ’74 machine showed that the first major step forward in motocross technology had been made.

1979 HONDA CR250R LAP TIME: 1:42

’81 SUZUKI RM250: RISING-RATE REAR SUSPENSION

In the early ‘80s the increasing popularity of supercross changed everything. Man-made tracks called for suspension that offered better control at low speeds and greater bottoming resistance. Manufacturers realized that single shock, linkage-operated rear suspensions were the answer. Unfortunately, most didn’t get it right–not at first. Early linkage bikes had terribly ineffective linkage curves and generally off-target shock settings. Suzuki, on the other hand, got its very first linkage system to offer good suspension performance, and it delivered all the mass-centralization and ergonomic benefits of a single, centrally located shock. The ‘81 RM250 was much slimmer than a machine with moved-up dual shocks and, with less weight away from the center of the bike, it was easier to maneuver on the ground and in the air. There weren’t any big breakthroughs at the front of the ’81 Suzuki. Like many late-’70s and early-’80s machines, it used air pressure in the fork to assist soft, heavily preloaded springs. The system gave the fork unnecessary stiction.

The RM’s engine was still air-cooled in ’81, but its power delivery showed a supercross influence. There was a lot of muscle at the bottom and in the midrange, so the bike jetted forward, even from very low speeds. With no power valve to help extend the top-end, the engine went noticeably flat at high revs. Everyone who rode the Suzuki thought its lap times would crush the ’79 Honda’s. It was a more pleasurable, willing mount to ride in many ways, but the difference wasn’t very big on the stopwatch.

1981 SUZUKI RM250 LAP TIME: 1:39

’87 HONDA CR250R: POWER-VALVE, LIQUID COOLING, DISC BRAKES, CARTRIDGE FORK

A lot of innovations came quickly in the early ‘80s. First, it was liquid-cooling. Then, with Yamaha leading the way, power valves and reeds became universal. In an attempt to put factory machinery on a closer level to what was available to privateers, the AMA’s ’86 production rule required stock frames, engine cases and bodywork. Thus, ’86-and-Iater production machines reflected a near-works level of technology. Frames and swingarms were made more rigid than they had ever been. By 1987, Honda was already on its second generation powervalve, having abandoned the ineffective ATAC system after a short run. The ’86 and ’87 Honda 43mm conventional cartridge fork lacked the rigidity of today’s massive front ends, but delivered excellent ride quality. It represented a major step forward in performance and adjustability from the comparatively crude damper-rod forks that were common in the early ’80s. The rear suspension was very nearly as good as what is available today. Advances were also made in ergonomics and weight distribution, but the biggest and most under-rated change of all was in brakes. By 1987 Honda and most other manufacturers were using both front and rear hydraulic disc brakes, which were outstanding. Out on the track, the ’87’ s relationship to current motocross bikes was unmistakable.

In rough terrain, this bike had the solid, planted feeling common to current motocross bikes. Responsive, quick-building power let the ’87 CR bolt out of turns and negotiate jumps in ways the non-power-valve-engined bikes couldn’t. The bike felt faster and more relaxed all around the track–a quality that helped it turn laps an impressive two seconds faster than the RM. In a ten-lap race, the ’87 CR could open up a devastating lead on the’ 81 RM.

1987 HONDA CR250R LAP TIME: 1:38

’89 YAMAHA YZ250: INVERTED FORKS

Unlike some of the other machines in our comparison, the ’89 YZ didn’t look vastly different from the bikes of the preceding era. The frame configurations were roughly the same. Similar rear suspension linkages were used. They were liquid-cooled, power-valved, two-strokes. The biggest difference was the Yamaha’s inverted fork. With the large aluminum tubes held by the triple clamps, the fork made the YZ front end far more rigid than the conventional fork it replaced. The results weren’t all good. Steering response is more direct, but the rider felt impacts that had been dulled by fork flex. Slap landings and square edges also come through more harshly. One benefit was that the inverted design greatly reduced the amount of fork underhang below the axle.

Some less visible differences between the machines were the advancements in ergonomics and weight distribution. The YZ’s radiators were lower and its fuel tank was flatter and narrower than the ’87 CR250R’s. Flicking the YZ from side to side and moving up on its tank to weight the front end was easier but the difference wasn’t dramatic. Same-year bikes from different manufacturers have felt as different.

Out on the track and on the clock, the YZ managed lap times that were quicker than the CR’s, but this didn’t happen consistently. When the ’89 beat the ’87, the differences were the smallest recorded between any two machines from successive eras.

1989 YAMAHA YZ250 LAP TIME: 1:38

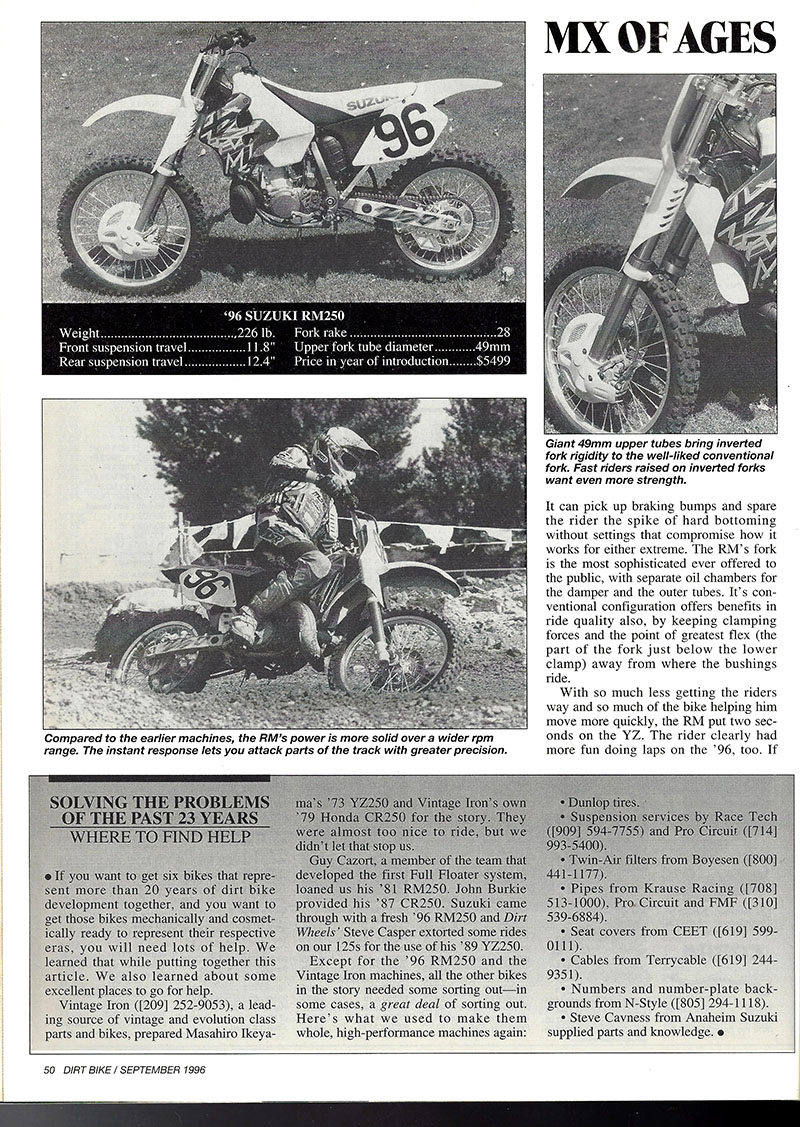

’96 SUZUKI RM250: MODERN REFINEMENT

You have run into them: riders who believe bikes haven’t improved much in recent years. Usually, they spend considerable time convincing themselves that the advancements of the recent past are meaningless. Power? They will say their bikes have more than any sane individual could possibly need! Suspension? They have never ridden better. Their brakes are awesome. At the end of their dissertations on the worthiness of older bikes, they will say the differences in the new bikes are only perceptible to pros. While it’s true that the gradual improvements in power and ergonomics mean more to more advanced riders, there’s simply no way anyone, regardless of skill level, can hop off a ’96 after riding something older without feeling faster, more comfortable and more in control. Suzuki’s ’96 RM250 delivered an unmistakable sensation of new-bike superiority.

It started with ergonomics. Nothing on the RM stopped you from moving about on the machine and all the controls operated with a light touch. The ’89 Yamaha’s shape and control feel were far less accommodating. The Suzuki’s solid, always-on power delivery made all your plans to negotiate bumps and jumps come together quicker and more predictably than on the ’89 Yamaha. The RM’s kind of power simply wasn’t available on stock bikes in ’89. Even in modified form, the Yamaha’s suspension can’t match the smooth operation of the RM fork and shock. The RM suspension, especially the fork, has a broader range of capability than the YZ’s. It can pick up braking bumps and spare the rider the spike of hard bottoming without settings that compromise how it works for either extreme. The RM’s fork was the most sophisticated ever offered to the public, with separate oil chambers for the damper and the outer tubes. I still had a conventional configuration, which offered benefits in ride quality also, by keeping clamping forces and the point of greatest flex (the part of the fork just below the lower clamp) away from where the bushings ride. With so much less getting the riders way and so much of the bike helping him move more quickly, the RM put two seconds on the YZ. The rider clearly had more fun doing laps on the ’96, too.

1996 SUZUKI RM250 LAP TIME: 1:36

The fact that the newer bikes were faster didn’t surprise anyone. As is often the case in the evolution of technology, all the giants were slain early, then it was a matter of incremental improvement. If we learned anything, it’s that we don’t always understand or appreciate technological advancement as it occurs. Often, it takes the perspective that the passage of time can offer.

Comments are closed.